Banish Belly Fat

June 1, 2012 Written by JP [Font too small?]When news outlets cover the current state of health care and weight, an image of a heavy-set person with a particularly large midsection is often featured. Due to recent changes in diet and exercise patterns, abdominal obesity has become increasingly common in the population at large. No longer does the term “beer belly” primarily apply to those who are problem drinkers. Nor does youth protect against it, as evidenced by higher rates of central obesity and metabolic syndrome frequently found in adolescents.

There are a number of suspects that have been implicated in this dangerous lifestyle related trend. Increased intake of high glycemic carbohydrates and fructose are frequently cited. A significant decline in physical activity, poorly managed stress and persistent sleep apnea are other likely contributors. And, while a comprehensive approach to reducing belly fat is best, there is at least one simple step that can jump start the process toward a slimmer core. Best of all, the strategy I’m referring to can be incorporated into most wellness routines with little cost, effort or risk.

The February 2012 issue of the journal Obesity examined the effects of dietary factors and physical activity in relation to abdominal fat in a group of over 11,000 adults. The authors of the 5 year study employed computed tomography, diet and exercise questionnaires in attempt to document meaningful patterns. Their findings indicate that two factors were most important in influencing the accumulation of visceral adipose tissue (VAT): 1) soluble fiber intake; 2) “vigorous physical activity”. Specifically, they determined that for each 10 gram increase in soluble fiber there was a 3.7% reduction in VAT. Several other population studies spanning the past decade have also drawn a consistent correlation between dietary fiber intake and abdominal fat and/or waist circumference. The take home message is that greater consumption of dietary fiber lowers the incidence of fat around the midsection. Another persistent pattern in the noted studies is that this dietary philosophy also tends to reduce the incidence of pre-diabetic and pre-heart disease risk factors collectively known as metabolic syndrome.

Researchers in the field offer a few clues about how and why fiber discourages the accumulation of belly fat. For one thing, the addition of dietary fiber to meals and snacks generally lowers the glycemic index (GI). Lower GI foods promote more stable blood sugar levels and lesser insulin and triglyceride production which, in turn, discourages fat deposition. Animal studies go on to reveal that the addition of supplemental fiber helps normalize diet and obesity-induced abnormalities found in rats with metabolic syndrome – namely, elevated inflammation (TNF-alpha) and low adiponectin. So, while fiber is helping to reign in your belly, it’s also protecting against the damaging consequences of central obesity while it’s still present.

If you’re ready to embark on a high fiber diet, here is my top ten list of foods and ingredients to get you started: Almonds (3 grams of fiber/oz), Avocado (10 grams/cup), Broccoli (5 grams/cup), Chia Seeds (11 grams/oz), Cocoa Powder (9 grams/oz), Collard Greens (5 grams/cup), Pumpkin (7 grams/cup), Purity Bread (8 grams/slice), Raspberries (8 grams/cup) and Flax Seeds (8 grams/oz). Please note that some of the figures (broccoli, collard greens and pumpkin) are reflective of the nutritional values of canned or cooked versions of these foods. Enjoy!

Note: Please check out the “Comments & Updates” section of this blog – at the bottom of the page. You can find the latest research about this topic there!

To learn more about the studies referenced in today’s column, please click on the following links:

Study 1 – Lifestyle Factors and 5-Year Abdominal Fat Accumulation … (link)

Study 2 – Dietary Determinants of Changes in Waist Circumference Adjusted … (link)

Study 3 – Whole-Grain Intake and Cereal Fiber Are Associated with Lower … (link)

Study 4 – Nutritional Evaluation in Mexican Postmenopausal Women with … (link)

Study 5 – The Effects of a Whole Grain–Enriched Hypocaloric Diet … (link)

Study 6 – Nutritional Risk and the Metabolic Syndrome in Women … (link)

Study 7 – Prospective Study of the Association of Changes in Dietary Intake … (link)

Study 8 – Glycemic Index Predicts Individual Glucose Responses … (link)

Study 9 – Plantago Ovata Husks-Supplemented Diet Ameliorates Metabolic … (link)

Study 10 – Postprandial Triglyceride Response in Men: Role of Overweight … (link)

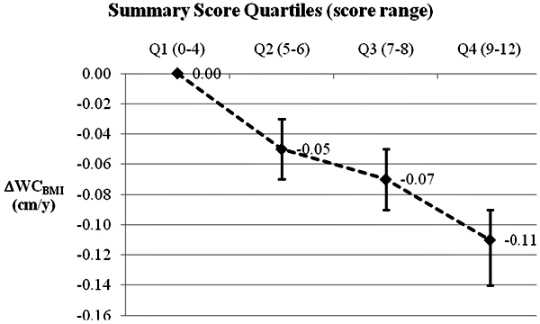

High Fiber Diets Are Linked to Lower Waist Circumference

Source: PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e23384. (link)

Tags: Body Fat, Fiber, Metabolic Syndrome

Posted in Diet and Weight Loss, Food and Drink, Nutrition

June 3rd, 2012 at 4:48 pm

Hi JP,

Interesting points you bring up. I wonder over time whether or not the food and drink we overconsume results in our bodies accumulating fat in different areas than, let’s say 100 years ago.

In particular, I see now obese teenage boys with bigger breast areas than what I remember from my own youth and seeing obese teenagers.

High fructose corn syrup? Environmental disturbers in the food/drinks?

I also think about obese Europeans. Wonder if they are gaining fat in the same areas as obese Americans. No HFCS in France-and less, (maybe) endocrine disturbers.

June 3rd, 2012 at 6:28 pm

Hi Mary.

IMO, there are multiple contributors to the growing problem of abdominal obesity. Several of them can be traced to (relatively) recent changes in the way most people live their lives. Youngsters, in particular, engage in less physical activity, eat more refined carbs and sugar and report one form or another of troubled sleep. From a biochemical standpoint, increased cortisol, insulin resistance and systemic inflammation could very well be at the heart of this modern health threat. Environmental influences (endocrine disruptors) are probably playing some role as well.

The good news is that this tide can likely be turned by implementing some common sense measures: a low glycemic, whole food diet, daily exercise, sleep hygiene and stress management. Taking reasonable steps to limit suspected toxins would also be prudent (and not that difficult to do). Just my two cents worth. 🙂

Be well!

JP

June 4th, 2012 at 8:09 am

Thanks JP ! Informative (as usual :))

Have a good day

June 4th, 2012 at 2:43 pm

I find it irritating when I see how people make being healthy so compictated

I think that its so easy people dont believe it, how if you just eat the foods meant for your body and become more active thats all you need, and sleep more. But it seems people will always believe a gimmick or a supplement when it comes to this, always looking for a quick fix

March 14th, 2015 at 2:43 pm

Update: Higher protein diets may lower risk of cardiometabolic disease …

http://jn.nutrition.org/content/145/3/605.abstract

J Nutr. 2015 Mar;145(3):605-14.

Higher-Protein Diets Are Associated with Higher HDL Cholesterol and Lower BMI and Waist Circumference in US Adults.

BACKGROUND: Protein intake above the RDA attenuates cardiometabolic risk in overweight and obese adults during weight loss. However, the cardiometabolic consequences of consuming higher-protein diets in free-living adults have not been determined.

OBJECTIVE: This study examined usual protein intake [g/kg body weight (BW)] patterns stratified by weight status and their associations with cardiometabolic risk using data from the NHANES, 2001-2010 (n = 23,876 adults ≥19 y of age).

METHODS: Linear and decile trends for association of usual protein intake with cardiometabolic risk factors including blood pressure, glucose, insulin, cholesterol, and triglycerides were determined with use of models that controlled for age, sex, ethnicity, physical activity, poverty-income ratio, energy intake (kcal/d), carbohydrate (g/kg BW) and total fat (g/kg BW) intake, body mass index (BMI), and waist circumference.

RESULTS: Usual protein intake varied across deciles from 0.69 ± 0.004 to 1.51 ± 0.009 g/kg BW (means ± SEs). Usual protein intake was inversely associated with BMI (-0.47 kg/m(2) per decile and -4.54 kg/m(2) per g/kg BW) and waist circumference (-0.53 cm per decile and -2.45 cm per g/kg BW), whereas a positive association was observed between protein intake and HDL cholesterol (0.01 mmol/L per decile and 0.14 mmol/L per g/kg BW, P < 0.00125). CONCLUSIONS: Americans of all body weights typically consume protein in excess of the RDA. Higher-protein diets are associated with lower BMI and waist circumference and higher HDL cholesterol compared to protein intakes at RDA levels. Our data suggest that Americans who consume dietary protein between 1.0 and 1.5 g/kg BW potentially have a lower risk of developing cardiometabolic disease. Be well! JP

October 2nd, 2018 at 1:58 pm

Updated 10/02/18:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6107686/

Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2018 Aug 17;9:466.

Twelve Weeks of Yoga or Nutritional Advice for Centrally Obese Adult Females.

Background: Central obesity is associated with a higher risk of disease. Previously yoga reduced the BMI and waist circumference (WC) in persons with obesity. Additional anthropometric measures and indices predict the risk of developing diseases associated with central obesity. Hence the present study aimed to assess the effects of 12 weeks of yoga or nutritional advice on these measures. The secondary aim was to determine the changes in quality of life (QoL) given the importance of psychological factors in obesity. Material and Methods: Twenty-six adult females with central obesity in a yoga group (YOG) were compared with 26 adult females in a nutritional advice group (NAG). Yoga was practiced for 75 min/day, 3 days/week and included postures, breathing practices and guided relaxation. The NAG had one 45 min presentation/week on nutrition. Assessments were at baseline and 12 weeks. Data were analyzed with repeated measures ANOVA and post-hoc comparisons. Age-wise comparisons were with t-tests. Results: At baseline and 12 weeks NAG had higher triglycerides and VLDL than YOG. Other comparisons are within the two groups. After 12 weeks NAG showed a significant decrease in WC, hip circumference (HC), abdominal volume index (AVI), body roundness index (BRI), a significant increase in total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol. YOG had a significant decrease in WC, sagittal abdominal diameter, HC, BMI, WC/HC, a body shape index, conicity index, AVI, BRI, HDL cholesterol, and improved QoL. With age-wise analyses, in the 30-45 years age range the YOG showed most of the changes mentioned above whereas NAG showed no changes. In contrast for the 46-59 years age range most of the changes in the two groups were comparable. Conclusions: Yoga and nutritional advice with a diet plan can reduce anthropometric measures associated with diseases related to central obesity, with more changes in the YOG. This was greater for the 30-45 year age range, where the NAG showed no change; while changes were comparable for the two groups in the 46-59 year age range. Hence yoga may be especially useful for adult females with central obesity between 30 and 45 years of age.

Be well!

JP